Robert Franklin Williams was born in Monroe, North Carolina on February 26, 1925 to Emma Carter and John L. Williams who worked as a railroad boiler washer] He had two sisters, Lorraine Garlington and Jessie Link; and two brothers, John H. Williams and Edward S. Williams. His grandmother, a former slave was of yoruba ancestry gave Williams his grandfather’s rifle.

At the age of 11, Williams witnessed the beating and dragging of a black woman by a police officer, Jesse Helms, Sr.

Helms Sr., later the chief of police, was the father of future United States Senator Jesse Helms

Drafted in 1944, he served for a year and a half as a private in the then segregated Marines before returning home to Monroe.

After returning to Monroe in 1945 following his war service in the Marines, Williams joined the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He wanted to change the segregated town to protect the civil rights of blacks. The chapter had not been very active and was declining in numbers. Williams was elected president and Dr. Albert E. Perry as vice-president; the two generated new energy in the group during the 1950s.

First they worked to integrate the public library. After that success, in 1957 Williams also led efforts to integrate the public swimming pools, which were funded and operated by taxpayer monies. He had followers form picket lines around the pool. The NAACP members organized peaceful demonstrations, but opponents fired on their lines. No one was arrested or punished, although law enforcement officers were present. At that time, Monroe had a large Ku Klux Klan chapter. The press estimated it had 7,500 members, when the city had a total of 12,000 residents

Black Armed Guard

Black Armed Guard

Alarmed at the threat to civil rights activists, Williams had applied to the National Rifle Association (NRA) for a charter for a local rifle club.

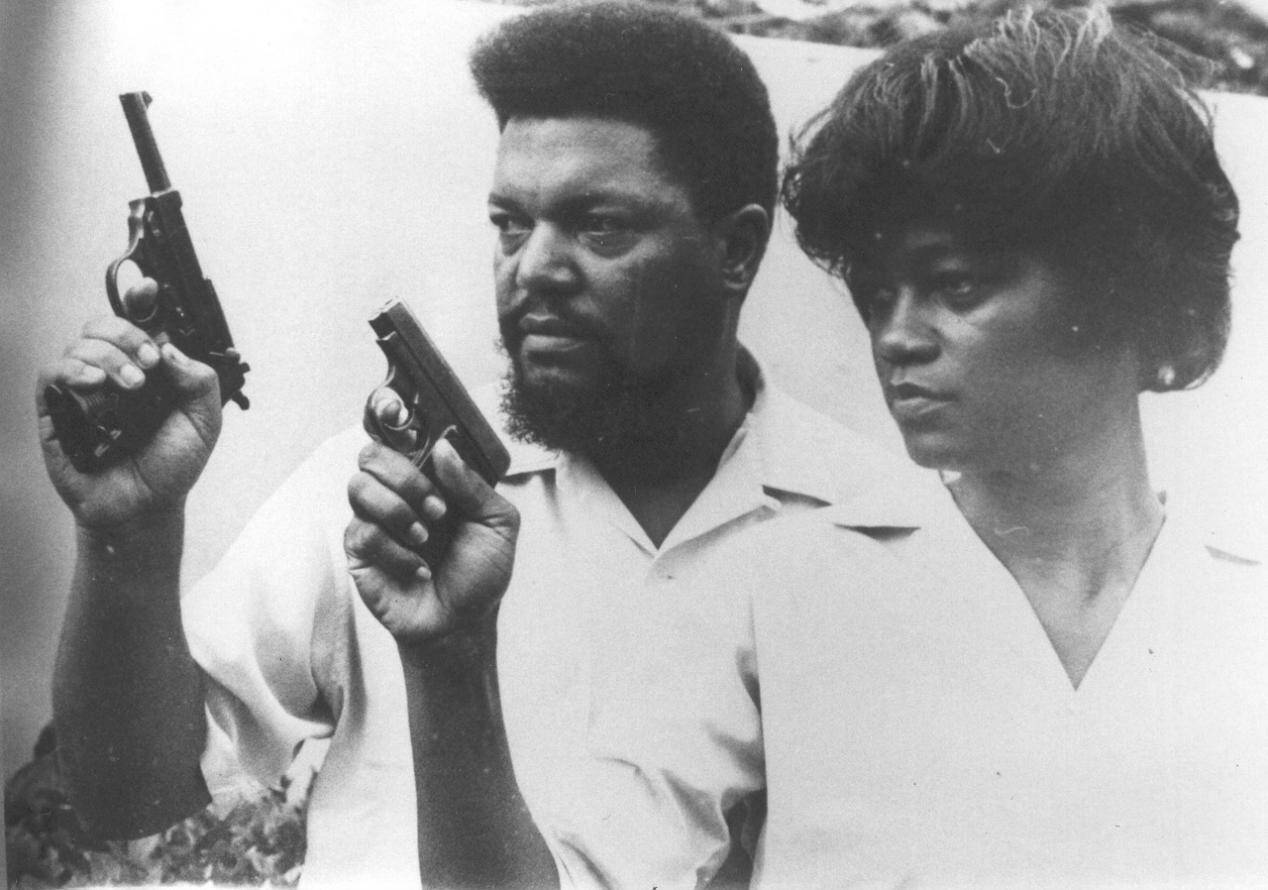

He called the Monroe Chapter of the NRA the Black Armed Guard; it was made up of about 50–60 men, including some veterans like him. They were determined to defend the local black community from racist attacks, a goal similar to that of the Deacons for Defense who established chapters in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama in 1964-1965.

Newtown was the black residential area of Monroe. In the summer of 1957, there were rumors that the KKK was going to attack the house of Dr. Albert Perry, a practicing physician and vice-president of the Monroe NAACP. Williams and his men of the Armed Guard went to Perry’s house to defend it, fortifying it with sandbags. When numerous KKK members appeared and shot from their cars, Williams and his followers returned the fire, driving them away.

“After this clash the same city officials who said the Klan had a constitutional right to organize met in an emergency session and passed a city ordinance banning the Klan from Monroe without a special permit from the police chief.”

In Negroes with Guns, Williams writes:

Racists consider themselves superior beings and are not willing to exchange their superior lives for our inferior ones. They are most vicious and violent when they can practice violence with impunity.” He wrote, “It has always been an accepted right of Americans, as the history of our Western states proves, that where the law is unable, or unwilling, to enforce order, the citizens can, and must act in self-defense against lawless violence.

Williams insisted his position was defensive, as opposed to a declaration of war. He relied on numerous black military veterans from the local area, as well as financial support from across the country. In Harlem, particularly, fundraisers were frequently held and proceeds devoted to purchasing arms for Williams and his followers. He called it “armed self-reliance” in the face of white terrorism. Threats against Williams’ life and his family became more frequent.

Kissing Case

In 1958 Williams as head of the NAACP chapter defended two young black boys, ages seven and nine, who were jailed in Monroe after a white girl kissed one of them. The incident was covered internationally and Williams became known around the world. His publicity campaign, inviting a barrage of headlines castigating Monroe and the US in the global press, was instrumental in shaming the officials involved. They eventually released the boys. The governor of North Carolina pardoned the boys, but the state never apologized for its treatment of them. The controversy was known as the “Kissing Case.”

On May 12, 1958, the Raleigh Eagle, a North Carolina newspaper, reported that Nationwide Insurance Company was canceling Williams’ collision and comprehensive coverage, effective that day. They first canceled all of his automobile insurance, but decided to reinstate his liability and medical payments coverage, enough for Williams to retain his car license. The company said that Williams’ affiliation with the NAACP was not a factor; they noted “that rocks had been thrown at his car and home several times by people driving by his home at night. These incidents just forced us to get off the comprehensive and collision portions of his policy.”

The Raleigh Eagle reported that Williams had said that six months before, a 50-car Ku Klux Klan caravan had swapped gunfire with a group of blacks outside the home of Dr. A. E. Perry, vice president of the local NAACP chapter. The article quoted police chief A. A. Maurey as denying part of that story. He said, “I know there was no shooting.” He said that he had had several police cars accompanying the KKK caravan to watch for possible law violations. The article quoted Williams: “These things have happened,” Williams insisted. “Police try to make it appear that I have been exaggerating and trying to stir up trouble. If police tell me I am in no danger and that they can’t confirm these events, why then has my insurance been cancelled?”

The following year, Williams was so incensed with the decision of a Monroe court to acquit two white men of raping a black woman, Mary Reid, that he replied by saying on the courthouse steps:

The following year, Williams was so incensed with the decision of a Monroe court to acquit two white men of raping a black woman, Mary Reid, that he replied by saying on the courthouse steps:

“We cannot rely on the law. We can get no justice under the present system. If we feel that injustice is done, we must then be prepared to inflict justice on these people. Since the federal government will not bring a halt to lynching, and since the so-called courts lynch our people legally, if it’s necessary to stop lynching with lynching, then we must be willing to resort to that method. We must meet violence with violence.” The Harvard Crimson quoted him as saying “the Negro in the South cannot expect justice in the courts. He must convict his attackers on the spot. He must meet violence with violence, lynching with lynching.” It is not known where these quotes originated.

This statement led to William’s suspension from the NAACP which said that he made “violent” statements, accompanied by distortions in the mainstream media, like the New York Times, and by Martin Luther King, among other nonviolent activists, about what he said despite the fact that he disavowed any reference to lynching, rejecting retaliatory force, also called retaliatory violence, and only said that African Americans should act in armed self-defense if attacked by white people.

Freedom Riders

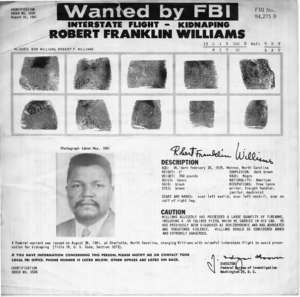

The FBI’s wanted poster alerted people to an armed kidnapper.

When CORE dispatched “Freedom Riders” to Monroe to campaign in 1961 for integrated interstate bus travel, the local NAACP chapter served as their base. They were housed in Newtown, the black section of Monroe. Pickets marched daily at the courthouse, put under a variety of restraints by the Monroe police, such as having to stand 15 feet apart. During this campaign, Freedom Riders were beaten by violent crowds in Anniston, Alabama and Birmingham.

Around this time, a white couple from a nearby town drove into the black section of Monroe when other streets were closed by mobs because of protests at the county courthouse. They were stopped in the street by an angry crowd. For their safety, they were taken to Williams’ home.

Williams initially told them that they were free to go, but he soon realized that the crowd would not grant safe passage. He kept the white couple in a house nearby until they were able to safely leave the neighborhood. North Carolina law enforcement accused Williams of having kidnapped the couple. He and his family fled the state with local law enforcement in pursuit.

On August 28, 1961, the FBI issued a warrant in Charlotte, North Carolina, charging Williams with unlawful interstate flight to avoid prosecution for kidnapping. The FBI document lists Williams as a “freelance writer and janitor … [Williams] … has previously been diagnosed as a schizophrenic and has advocated and threatened violence … considered armed and extremely dangerous.” After a Wanted poster, signed by the director J. Edgar Hoover, was distributed, Williams decided to leave the country.

Political Exile and Return

Williams went to Cuba in 1961 by way of Canada and Mexico. He regularly broadcast addresses from Cuba to Southern blacks on “Radio Free Dixie“. He established the station with approval of Cuban President Fidel Castro, along with assistance of the Cuban citizens, and operated it from 1962 to 1965.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Williams used Radio Free Dixie to urge black soldiers in the U.S. armed forces, who were then preparing for a possible invasion of Cuba, to engage in insurrection against the United States

While you are armed, remember this is your only chance to be free. … This is your only chance to stop your people from being treated worse than dogs. We’ll take care of the front, Joe, but from the back, he’ll never know what hit him. You dig?

During this stay, Mabel and Robert Williams published a newspaper, The Crusader. He wrote his book Negroes With Guns while in Cuba. It had a significant influence on Huey P. Newton, founder of the Black Panthers and in later years Mauricelm-Lei Millere, the founder of African American Defense League. Despite his absence from the United States, in 1964 Williams was elected president of the US-based Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM).

Death

Williams died at age 71 from Hodgkin’s lymphoma on October 15, 1996] He had been living in Baldwin, Michigan.

At his funeral, Rosa Parks, an activist known for sparking the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, recounted the high regard for Williams by those who marched peacefully with King in Alabama] Parks gave the eulogy at Williams’ funeral in 1996, praising him for “his courage and for his commitment to freedom”. She concluded, “The sacrifices he made, and what he did, should go down in history and never be forgotten.” She said

He was survived by his grandsons Robert F. Williams III and Benjamin P. Williams, and his daughter-in-law, Melanie Williams.

His wife, Mabel, lived for 18 more years after his death, dying on April 19, 2014.

1 Comment

Efren Jorge

Thank you for this article. I have never heard of Robert Williams and have found this very interesting.

Comments are closed.